← Back

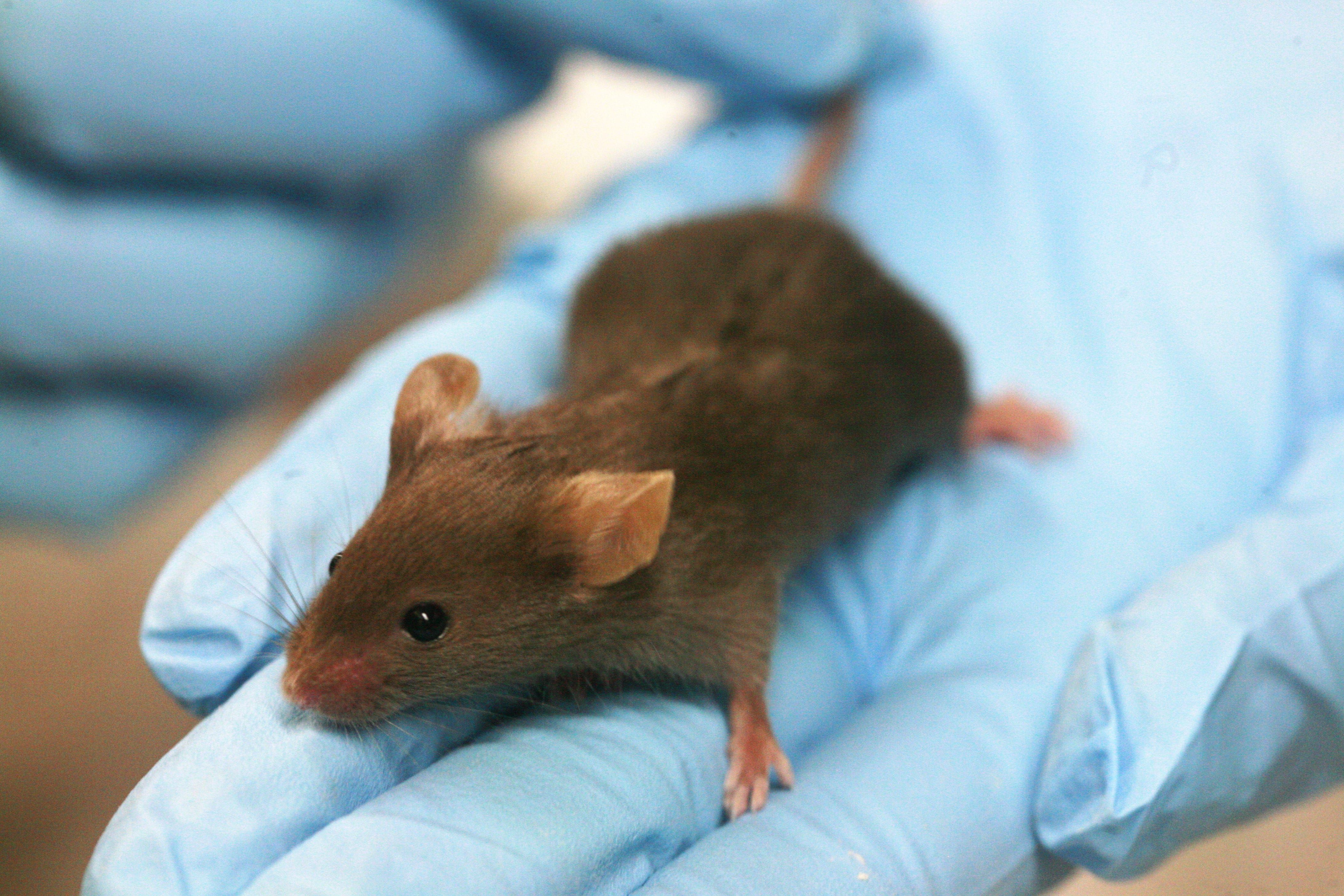

A recent vaping study on mice from UCSD’s School of Medicine and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System found, surprisingly, that mice don’t like to vape. The results showed that after being forced to inhale e-cig vapour for one hour a day for four weeks, that the vaping mice showed 10% more inflammation markers (signs of full-body inflammation) than their non-vaping companions.

What does this tell us definitively about the effects of vaping on humans? Absolutely nothing. The conclusion drawn by the lead scientist on the study is this: it “shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign”. Speaking more accurately, she should have said that “this study shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign for mice.” Because, as she (probably) knows there are a number of chemicals that are not benign for mice but helpful for humans and vice versa.

Jean-Marc Cavaillon, head of the cytokines and inflammation unit, points to one particular monoclonal antibody which treats lymphoma in mice but would send a human being to intensive care — an anti-inflammatory drug that cures rodents but kills humans. On the other hand, paracetamol and aspirin are both helpful to humans but deadly to mice. Thamaldihide, which eases morning sickness in pregnant women, doesn’t adversely affect mice but causes birth defects in humans. The spate of Thamaldihide-related birth defects in the 50s were a direct result of mice studies that failed to consider how the chemical might react differently in humans.

In fact, 95% of newly developed drugs that have looked promising after mice trials have failed to help humans.

A recent vaping study on mice from UCSD’s School of Medicine and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System found, surprisingly, that mice don’t like to vape. The results showed that after being forced to inhale e-cig vapour for one hour a day for four weeks, that the vaping mice showed 10% more inflammation markers (signs of full-body inflammation) than their non-vaping companions.

What does this tell us definitively about the effects of vaping on humans? Absolutely nothing. The conclusion drawn by the lead scientist on the study is this: it “shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign”. Speaking more accurately, she should have said that “this study shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign for mice.” Because, as she (probably) knows there are a number of chemicals that are not benign for mice but helpful for humans and vice versa.

Jean-Marc Cavaillon, head of the cytokines and inflammation unit, points to one particular monoclonal antibody which treats lymphoma in mice but would send a human being to intensive care — an anti-inflammatory drug that cures rodents but kills humans. On the other hand, paracetamol and aspirin are both helpful to humans but deadly to mice. Thamaldihide, which eases morning sickness in pregnant women, doesn’t adversely affect mice but causes birth defects in humans. The spate of Thamaldihide-related birth defects in the 50s were a direct result of mice studies that failed to consider how the chemical might react differently in humans.

In fact, 95% of newly developed drugs that have looked promising after mice trials have failed to help humans.

Are mice-based e-cigarette studies dangerously misleading?

In laboratories around the world, scientists are exposing mice to e-cigarette vapour to try and learn about the health benefits (or lack thereof) of e-cigarettes. But fundamental differences between the respiratory systems of man and mouse mean that this research has limited effectiveness...

A recent vaping study on mice from UCSD’s School of Medicine and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System found, surprisingly, that mice don’t like to vape. The results showed that after being forced to inhale e-cig vapour for one hour a day for four weeks, that the vaping mice showed 10% more inflammation markers (signs of full-body inflammation) than their non-vaping companions.

What does this tell us definitively about the effects of vaping on humans? Absolutely nothing. The conclusion drawn by the lead scientist on the study is this: it “shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign”. Speaking more accurately, she should have said that “this study shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign for mice.” Because, as she (probably) knows there are a number of chemicals that are not benign for mice but helpful for humans and vice versa.

Jean-Marc Cavaillon, head of the cytokines and inflammation unit, points to one particular monoclonal antibody which treats lymphoma in mice but would send a human being to intensive care — an anti-inflammatory drug that cures rodents but kills humans. On the other hand, paracetamol and aspirin are both helpful to humans but deadly to mice. Thamaldihide, which eases morning sickness in pregnant women, doesn’t adversely affect mice but causes birth defects in humans. The spate of Thamaldihide-related birth defects in the 50s were a direct result of mice studies that failed to consider how the chemical might react differently in humans.

In fact, 95% of newly developed drugs that have looked promising after mice trials have failed to help humans.

A recent vaping study on mice from UCSD’s School of Medicine and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System found, surprisingly, that mice don’t like to vape. The results showed that after being forced to inhale e-cig vapour for one hour a day for four weeks, that the vaping mice showed 10% more inflammation markers (signs of full-body inflammation) than their non-vaping companions.

What does this tell us definitively about the effects of vaping on humans? Absolutely nothing. The conclusion drawn by the lead scientist on the study is this: it “shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign”. Speaking more accurately, she should have said that “this study shows that e-cigarette vapour is not benign for mice.” Because, as she (probably) knows there are a number of chemicals that are not benign for mice but helpful for humans and vice versa.

Jean-Marc Cavaillon, head of the cytokines and inflammation unit, points to one particular monoclonal antibody which treats lymphoma in mice but would send a human being to intensive care — an anti-inflammatory drug that cures rodents but kills humans. On the other hand, paracetamol and aspirin are both helpful to humans but deadly to mice. Thamaldihide, which eases morning sickness in pregnant women, doesn’t adversely affect mice but causes birth defects in humans. The spate of Thamaldihide-related birth defects in the 50s were a direct result of mice studies that failed to consider how the chemical might react differently in humans.

In fact, 95% of newly developed drugs that have looked promising after mice trials have failed to help humans.